Step slowly. Deliberately. Feel the undergrowth brush against your bare calves; let every sprig, twig and barb carve a gallery of symbols onto your skin. A daub of pollen here, a bloody scratch there, all messages from Australia's past handed down for thousands of years from those who have walked this way before.

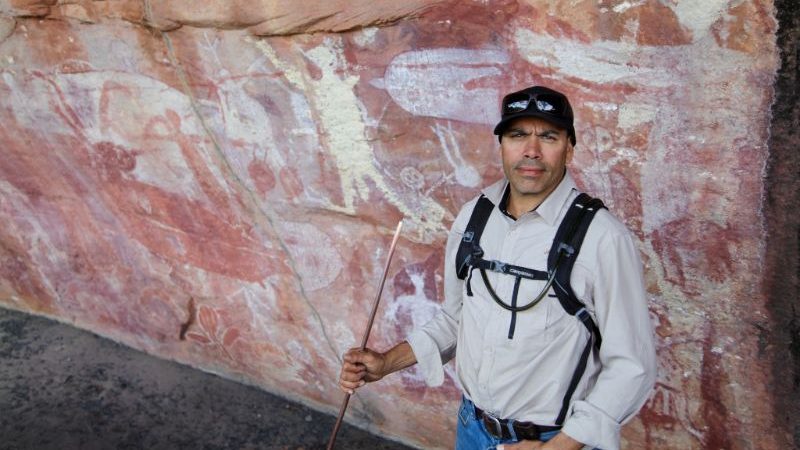

Stop. Look up to the purple sky, and listen; to the song of the bush lark, the craw of the currawong, the call of the kookaburra. Follow the avian orchestra as it draws you into a rock shelter, its underside aglow with painted Quinkan spirits, their long limbs seeming to dance like shadow puppets. Feel the hair on your arms stand to attention as you listen to a First Nations custodian share Dreamtime stories about his country.

“Dreamtime stories represent a connection to country and place,” says Johnny Murison. “When you look at country it's not just hills, rocks and plants, the whole landscape takes on meaning because you've got the stories.”

I'm on Quinkan country, homeland of the Kuku-Yalanji, the ‘rainforest' people of Queensland's Cape York Peninsula. As Johnny shares his Dreamtime story about the red owl Nurrku I grab the information and fold it into my heart like a love letter.

I have spent years travelling the length and breadth of the country, gathering these gifts, trying to pull together pieces of a larger puzzle. Not only to better understand the connection First Nations people have with country, but to find my own place in it.

Aboriginal heritage

I'd always known I was of Aboriginal descent - there was no denying my grandmother's dark skin or her lively stories about her bush childhood. In contrast I'd grown up in a Housing Commission estate in the western suburbs of Sydney, raised by my single mother and grandmother who rarely spoke of our Aboriginal heritage.

After my Nan's passing I received confirmation that she was a descendant of the Awabakal people from the mid-north coast of New South Wales. At first I could barely whisper the word - Awabakal. A bright word that tastes of salt and brine and shellfish. Now I say it with pride. Referred to as ‘flat water people' (Awaba is the word for Lake Macquarie) the Awabakal nation stretches from the coast to the Hunter River to the Watagan Mountains. The wedge-tailed eagle is their identity symbol.

One continent, many nations

Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people - a term used to describe the Aboriginal peoples of mainland Australia and Tasmania and the Indigenous people of the Torres Straits - represent the world's oldest living culture.

And not just one culture, but hundreds of different nations and clans, each as distinct as the countries of Europe with their own language, customs, stories and lore.

From saltwater to desert to mountain country there is one shared belief that unites all Aboriginal people - connection to country. To Australia's First Nations people, land is not something to be owned, rather it is the link between all aspects of existence - identity, spirituality, family, language and culture. Travel has opened my eyes to the beauty of this spiritual connection to land and taught me to be grateful for this unbroken chain of custodianship, which has survived for more than 65, 000 years.

Learning to connect to country

Without exception, all the Aboriginal guides I have met talk about country as if it were a person. To be longed for, worried about, taken care of and respected.

It was on a kayaking tour of Western Australia's World Heritage-listed Shark Bay - known as Gutharragunda in the local Malgana language - that I learnt about the traditional owners' connection to the world-famous stromatolites at Hamelin Pool. As I paddled the clear waters of Big Lagoon my guide Darren “Capes” Capewell explained that the Malgana people referred to the stromatolites as their “old people”. Now, wherever I travel on country I pause to feel the spirits of the ancestors. They live in the graceful limbs of a ghost gum, in the chuckle of a desert breeze, and in the weathered faces of a rock wall.

I've connected to country through food: from snacking on zesty green ants during bush tucker tours, to sipping the nectar of golden grevillea flowers on a multi-day hike. I've hunted crabs on the traditional lands of the Kuku-Yalanji people on Queensland's Cooya Beach and feasted on barbecued ‘roo tail in the Simpson Desert. While these travel experiences have brought me closer to the land, they've also awakened some genetic memory, an ancestral whisper if you like, calling me to continue my own personal journey.

Dreamtime stories are also like that; a voice from the time when ancestral spirits roamed the earth, creating life and forming the natural environment. A voice that explains how to care for country and the rules that must be followed.

As Johnny talks about the Dreamtime stories connected with the red owl Nurrku, my eyes are drawn to the outline of a wedge-tailed eagle silhouetted against the enamel blue sky. Perhaps here, on the remote Cape York Peninsula, the bird the Awabakal people call Kon is continuing to watch over me.